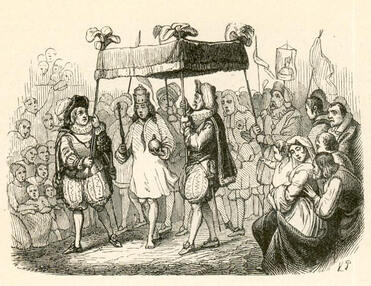

Don’t be gaslit. There is such a thing as cancel culture and it is pernicious and toxic. Sure, there are those who invoke “cancel culture” as a complaint when what they are really upset about is a legitimate consequence. But the fact that some people exaggerate the problem of cancel culture does not mean that it isn’t a problem. And, yes, it is a problem on both ends of the political spectrum and everywhere in between. It is a problem in the evangelical community. It’s a problem everywhere. There are so many ways to run afoul of the prevailing orthodoxy of whatever community you belong to and all of us are clamming up and editing our thought and speech out of self-preservation. And when that’s the case you get lots of instances of the “Emperor’s New Clothes.” In Hans Christian Andersen’s folktale, published in 1837, a pompous emperor is flattered by unscrupulous tailors into believing that he is donning a robe of such marvelous material and of such exquisite workmanship that only the truly astute and enlightened could even perceive it. Because no one wanted to be thought uncouth, the fiction was reinforced by general participation with everyone eager to obtain their bona fides by gushing their admiration for the beautiful robe. In our culture today there are lots of instances of the Emperor’s new clothes, with the difference being that if we refuse to participate in the fiction we risk more than contempt from those who are invested in it. There is the possibility of real censure. And lies are not more strong, but they do possess a different strength than truths. The strength of a lie is in its appeal to those who would like to believe it and in the dogmas that spring up to buttress them. Truth comes armed with the sharpest of all swords, but the lie shows up with an army, even if it’s only armed with butter knives. But here’s some good news for you. Those who possess the truth are also equipped with two related qualities: stubborn courage on the one hand, and mirth on the other. Those who perpetuate cancel culture are fearful and humorless. But when the church is more invested in the truth than in its place in the culture, it finds the courage to tell even unpopular truths and the mirth to chuckle at the preposterous lies. And nothing breaks the spell of a lie quite like honest laughter. When there is a sense that telling the truth could get you in trouble and there are people who are poised to pounce and punish you for your candor there are twin temptations. On the one hand we might want to shrink back, and on the other we might want to get shrill. But the church’s mandate is to be salt and light, to speak clarity and to add savor to the discourse. And we are not immune to the pressures of cancel culture. Even when the church owns its own building and belongs to a network of churches and enjoys constitutional protections, there are a lot of ways in which spiteful people could seek to punish the church for having the temerity to point out the emperor’s nakedness. But, nevertheless, the church is more insulated from cancel culture than many individuals and institutions and if you can’t get the truth from the church where will you hear it? So we don’t articulate these truths to pick a fight or wave a flag, and we don’t utter them through clenched teeth. The business of truth telling is not a grim endeavor but a cheerful project and we undertake it with impish freedom as though we were God’s own, good-natured provocateurs. So what truths do we have to tell? It is worth saying, for instance, that . . .

We could go on, but that gives you the idea. Some of these statements are things that people of good faith could legitimately dispute. Any of these statements might, from the right platform, incite a vindictive mob. But all of these statements are worth making as winsomely and lovingly as possible by the only ones who can be counted on to do so. If cancel culture is a poison, it is no remedy to purse your lips having inhaled the toxic fumes. The only antidote is the truth and its successful administration relies on open minds and open mouths.

0 Comments

What would you do with five carrots, a quart of new potatoes, a pint of cherry tomatoes, two bell peppers, a bunch of arugula, a dozen eggs and a bag full of some odd looking vegetable which you can no more pronounce the name of than guess a use for? Get a share in a CSA and you may end up asking yourself that question. Community Supported Agriculture, CSA for short, is an arrangement where customers support a local farm by paying at the beginning of a season for a share of the season’s produce. At its best the CSA benefits both the farmer, who gets the assurance of a timely income to insulate him from the ups and downs of farming, and the customer, who gets a steady but varied supply of fresh, nourishing, local produce. But CSA’s are not without their risks. If the weather is bad, if there’s a crop failure, if the foxes get your chickens the farmer and customer are left trying to make the most of a scanty supply of eggs and an abundant supply of zucchini, because there will always be zucchini. Let me tell you, as someone who has eaten at McDonalds and who has participated in CSA's, what some of the differences are. Hunger might make you pull into the drive-thru, but it takes a real desire to have a new relationship with food for you to sign up for a CSA. When it comes to fast food you are a consumer, and when it comes to the CSA you are a participant. At the fast food restaurant you can choose whatever you want off a menu you had no say in developing. With a CSA you get whatever the farmer provides (and nature permits) from a range of possibilities that you had some input into. With a fast food restaurant you get the comfort of consistency: your order will look and taste the same at any franchise in any season. With the CSA you have the charms and the challenges of variability, surprise, and seasonality: you must savor the fleeting blueberries and gamely accept the enduring rutabagas. Fast food often pleases better than it nourishes, and CSA’s often do a better job of nourishing than pleasing. Fast food involves no more effort than what’s required to eat the food and tip the tray into the waste bin. The arrival of your CSA order is the beginning of a great deal of effort: researching vegetables, looking up recipes, paring and peeling, cooking meals, putting produce up. There are plenty of differences. And none of this is to suggest that one approach to feeding people is superior to the other. Many people live in places where only one or the other approach is an option, while others happily take advantage of both. But if you are someone who is interested in feeding hungry people you cannot be both a fast food restaurant and a CSA. And this brings us to church. For generations and generations most people related to their community of faith along the lines of a CSA. They bought into the church, they subscribed, because they knew that the church needed their support to thrive and that a thriving church was essential to their own flourishing and that of their family and community. If there were spiritual seasons of abundance they would enjoy that bounty with the other members of the church. And if there were spiritual seasons of drought they would make that deprivation lighter by sharing it no less equally. The CSA approach to church meant that their preferences were only sometimes gratified. They had to make do with the share that the farmer/pastor gave them. And when they received that share it became apparent that all the work that had been done in the field would have to be met by a corresponding work in the kitchen if the value of the arrangement was to be fully realized. The pastor/parishioner relationship was not transactional and couldn’t afford any passivity on either end. But the same cultural forces that led to the rise of fast food restaurants resulted in the “McDonaldization” of American Christianity. People wanted efficiency, consistency, ease of consumption, and value. The old model of church did not provide those things. And so churches became programmatic franchisees and their parishioners became customers who came to order, a la carte, from glossy menus that were all very similar. And there were lots and lots of good things that came from that approach. Many thousands of souls have been “called out of darkness and into his marvelous light” through the ministry of such churches. And it has been, consciously or not, the model on which we have operated,more or less. But if this cultural moment gives us a unique opportunity to reconsider and recast our church, maybe we should give some thought to going back to the historic approach, to being a spiritual CSA with a life giving “farm stand” on main street. |

Furnace Brook Wesleyan Church Blog

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed